Edward Clark, Untitled #2 (“The Blue One”), (2004)

Written by Jimin Kim, BA in Art History and East Asian Languages and Civilizations, 2022 in collaboration with Roko Rumora, PhD Candidate Department of Art History

In Untitled #2 (“The Blue One”), three waves of large, continuous brushstrokes in varying shades of blue – turquoise, green-ish, and powder — blend into each other across the canvas, giving a new life to the background that was once in void.

The wavering motion of each brushstroke directs us to the method through which the painting was produced – “the big sweep” — the signature style of Ed Clark (1926-2019) cultivated throughout his six decades-long engagement with abstract expressionism. Upon plunging a push broom into dry, acrylic pigment, Clark would sweep a series of expansive brushstrokes with much strength and velocity, producing layers of seemingly horizontal lines that interact with one another. Such a distinct method allowed the artist to transform the push broom — a symbol of menial labor — into an invaluable instrument of abstraction in high art.

To Clark, the paint, born out of his physical sweeping of a broom, serves not only as a medium, but also as the only subject matter of his productions that explore the infinite possibilities of colors in abstraction.

Read More

The inception of “the big sweep,” or the so-called push broom technique, dates back to 1956 when Clark was living in Paris—a place to which he moved in search of relief from the racial discrimination he had faced in the United States. In an effort to cover sizeable areas with a single stroke in a short period of time, Clark initiated the use of a 48-inch push broom, the kind of a broom commonly used in custodial services. With such an unconventional tool, Clark pioneered his signature method of sweeping a single stroke across the width of a canvas placed on the floor.

According to Clark, in 1997 interview, the most integral aspect of his method was the “speed” of the act of sweeping the broom: “something really fast.. (almost) also an anger or something like that that go(es) through it in a big sweep.” The physical intensity and velocity of the manual process added a sense of spontaneity to his productions that was distinct from those of his abstract expressionist predecessors, whose primary modes of painting were dripping or staining.

After his decade-long stay in Paris, Clark relocated to New York where he actively engaged with the downtown art scene and founded the artist collective Brata in 1956, however, he return to Paris in the 1980s. During his years in New York, Clark continued to experiment with “the big sweep,” undergoing a series of stylistic changes. In 1957, he started experimenting with shaped canvases, which paved a way for him to create his signature elliptically-shaped paintings in 1968. In the following decades, he furthered his artistic experiment by producing more curved, less linear brush strokes with the push broom, extending the possibilities of his technique. In regard to Clark’s evolving stylistic development during this period, Darby English, the Carl Darling Buck Professor of Art History at the University of Chicago, remarks that Clark particularly engages with the “exhilarating openness of its color,” as well as the “intensity with which he was devising ingenious ways to achieve it.”

Produced in 2004, Untitled #2 (“The Blue One”) serves as an exemplar of Clark’s productions in that they had turned much simpler, freer, and smaller in size late in his career; the final destination of his enduring experiment with “the big sweep.”

Despite the pioneering qualities of Clark’s abstract expressionism, it was not until late in his life that he gained recognition in the mainstream discourse of Art History. Active in the late mid-20th century when African American artists were expected to produce figurative works, as opposed to the predominantly white demographic of abstract expressionists, scholarly discourses of the time failed to address Clark’s work in relation to his Caucasian counterparts. Aware of this, Clark held strong reservations about his practice being classified as ‘black art,’ rather than ‘abstract expressionist,’ preferring his art to be interpreted in the context of his genre, rather than that of his ethnic background.

Since the 2010s, Clark, as well as his African American abstract expressionist contemporaries, achieved presence in the scholarly discourse, followed closely by growing demand to further the examinations of their practices. In light of such conversations in the genre, the contemporary legacy of Ed Clark prevails in the works of his successors such as Mark Bradford, whose work Minutes are Painful (2016) is also currently exhibited at the Forum.

Artist Profile

Edward Clark

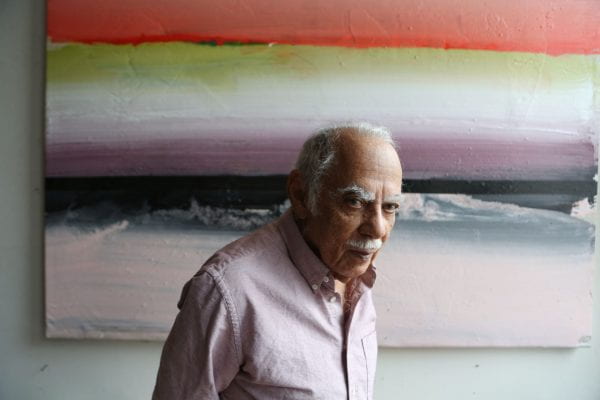

American, born 1926

Photo © Chester Higgins Jr/The New York Times/Redux

Written by Jimin Kim, BA in Art History and East Asian Languages and Civilizations, 2022 in collaboration with Roko Rumora, PhD Candidate Department of Art History

Chicago—the city in which the work is currently exhibited—is where Ed Clark’s early memories lie. Born in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1926, Clark spent his formative years in Chicago where he attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, taught by Louis Ritman and Edouard Goerg.

Although his practice during his early career had a stronger focus on figuration and representational imagery, his style had transformed into abstraction during his time in Paris in the early 1950s, when he invented the renowned “big sweep,” commonly referred to as the push broom technique.

This non-traditional method enabled Clark to push the boundaries of the abstract expressionist movement throughout his career, which spanned from the 1950s to the 2010s. Over the decades, Clark continuously experimented with the materiality of paint, abstract form, and colors, engendering multiple groundbreaking developments—one of which being the manipulation of the shape of the canvas from a conventional rectangular one to an eclipse-like oval form.

Related Links

Professor Darby English: 1971: A Year in the Life of Color

Ed Clark: A Brush with Success