©2019 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Takashi Murakami, Tan Tan Bo Black Hole (2019)

Written by Jimin Kim, BA in Art History and East Asian Languages and Civilizations, 2022

To those who recognize Murakami for his signature, joyful, anime-inspired characters, Tan Tan Bo Black Hole (2019) suggests a rather dark idea embedded in his practice: his apprehension of nuclear power.

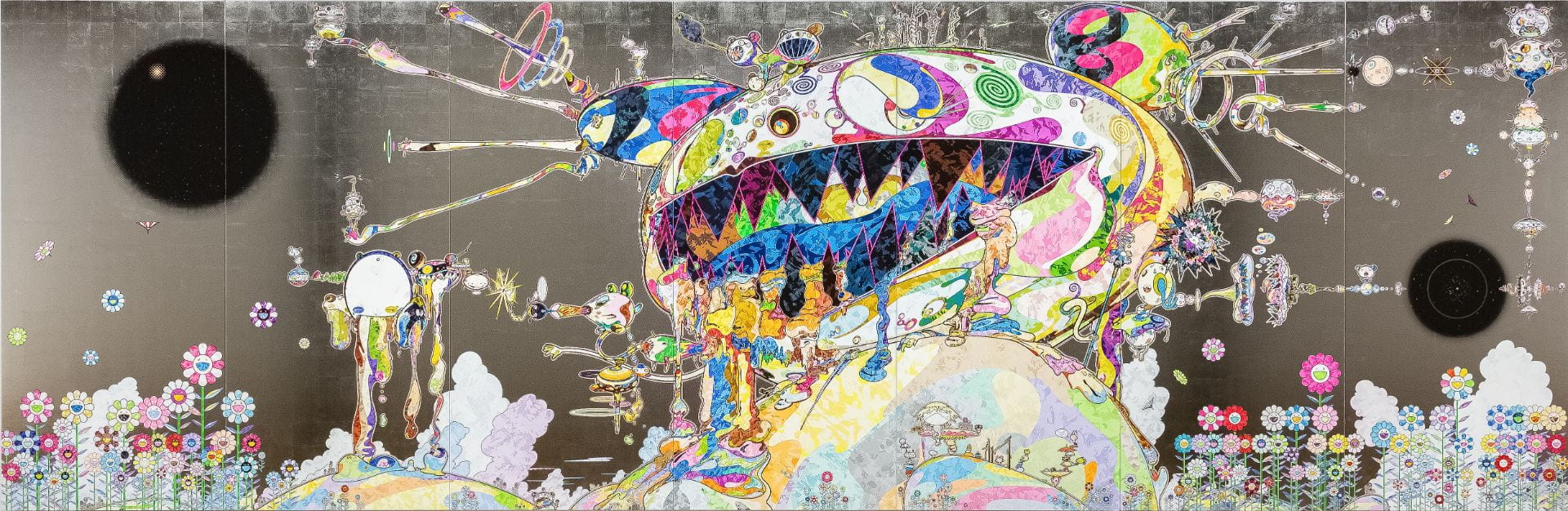

In the center of this multi-panel painting appears Tan Tan Bo, the unearthly version of Murakami’s alter ego Mr. DOB. With rays and multicolored biomorphic forms spewing and dripping from its mouth and ears, the character is portrayed as a continuous explosion of forms and colors, which may appear uncanny from a distance. However, a closer examination of the work reveals the alluring nature of the various magical icons meticulously illustrated on the surface, including the artist’s emblematic smiling daisies.

Distinct from the chaotic starbursts in the foreground are the gleaming black orbs at each end of the canvas—black holes punctuated by miniscule metallic flecks. Such forms become particularly notable when we understand Murakami’s long-standing engagement with nuclear disaster as a subject matter. On view at the institution where the world’s first artificial nuclear reactor was built, this work challenges us to critically reexamine the legacies of the invention, as well as its contemporary influences.

Read More

Beyond the apparent kawaii-ness—the quality of cuteness in Japanese culture—of Murakami’s brightly-colored anime characters, the enduring history of the artist’s interrogation of the contemporary realities of Japan prevails. Tan Tan Bo Black Hole (2019) is a continuation of the artist’s Tan Tan Bo series, which he started in the early 2000s, and illustrates the aftermath of nuclear disasters in Japan. What requires the viewer’s attention is the coexistence of two distinct qualities; while the full-scale work produces a sense of monstrosity, heightened by the grotesque illustration of Murakami’s alter ego Mr. DOB, close observation reveals the meticulous portrayal of small multi-colored manga-like figures which manifest a sense of fascination. Such disparity between the two facets captures what Murakami hints to as the dilemma of the Japanese society in the wake of nuclear disasters. According to the artist, individuals are “stuck in protective cocoons,” avoiding breaking out of the collective illusion that everything is in a good state when, in reality, the society is heading towards an apparent downfall.

A close examination of the painting reveals its “super flatness”—the sense of 2-dimensional planarity that extends throughout the canvas, granting an equal amount of detail to every figure presented on the screen. With his academic training in Nihonga, a traditional Japanese painting style, and continued interest in the interactions between art and non-art, Murakami unifies his aesthetic principles into the theory of the Superflat —a term he devised in 2001 to refer to the hyper-compressed surface he repeatedly produces in his paintings. Within his works, defined lines, bright colors, and digital imageries on a depthless 2-D screen manifest a sense of complete flatness. The hierarchal compositions and flatness in Murakami’s super flat paintings resemble Nihonga paintings from the Edo period, which encourage the viewer’s flowing eye movement across multiple screens. Murakami argues that such a super flatness is a visual representation of the “horizontal nature of Japanese culture” in which the boundaries between art and non-art, East and West, and high and low cultures have become essentially nonexistent.

The theory of super flatness not only encapsulates the ongoing convolutions of the various cultural elements that lie within the psyche of contemporary Japanese society, but also reminds the audience of the topographical flattening of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a result of the atomic bombings in August 1945. To the artist, the tragedy of nuclear disaster not only marked Japan’s transition into a post-war society after WWII, but also alarmed the disruptive threats of the world’s use of nuclear energy. Murakami returns to nuclear themes in his work to address his sympathy with the victims of recurrent nuclear disasters, as well as, his dissatisfaction with the “constrained nature of civil discourse in Japan” regarding the government’s treatment of the incidents.

The painting’s implication of the devastating social impacts of nuclear power provokes us to re-examine the worldwide use of nuclear power. Since the invention of the world’s first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction on December 2, 1942 at the University of Chicago, the Atomic Age has brought the combined promise and threat, engulfing us with both hope for scientific advancement and fear of natural disaster. The duality of the cuteness and darkness coexisting in Tan Tan Bo Black Hole (2019) perhaps directs us to the paradox of the development of nuclear power; the invention entails both destructivity and creativity, challenging us to question our place in mediating the opposing qualities of nuclear technology.

Artist Profile

Photo by Maria Ponce Berre

Takashi Murakami

Japanese, born 1962

Written by Jimin Kim, BA in Art History and East Asian Languages and Civilizations, 2022

Takashi Murakami (b. 1962) is a Tokyo- and New York-based artist and entrepreneur renowned for his pioneering practice in blurring the lines between highbrow and popular culture; tradition and the contemporary; and East and West. Upon receiving a BA, MFA, and PhD in Nihonga, traditional Japanese painting, from the Tokyo University of the Arts, Murakami has integrated his academic background with his passion for Japanese animations and comics, most notably through his signature Superflat style that synthesize his cartoon-inspired characters with traditional Japanese aesthetic principles. In 1996, he furthered his artistic experiment by establishing a factory-like studio called Hiropon Factory, now referred to as Kaikai Kiki Co. Ltd., where he works with a large staff of assistants to mass-produce items featuring his trademark figures, frequently collaborating with high-end fashion brands that also challenge the conventional binaries of high and low art. In addition to exploring the ideas of art and non-art in his practice, Murakami engages with the contemporary societal conditions of his home country, especially since the Tohoku earthquake of 2011 and the subsequent nuclear incident in Fukushima.

Related Links

Department of Physics: The Manhattan Project

Professor Chelsea Foxwell: Making Modern Japanese-Style Painting

Smart Museum of Art: Art to Live With