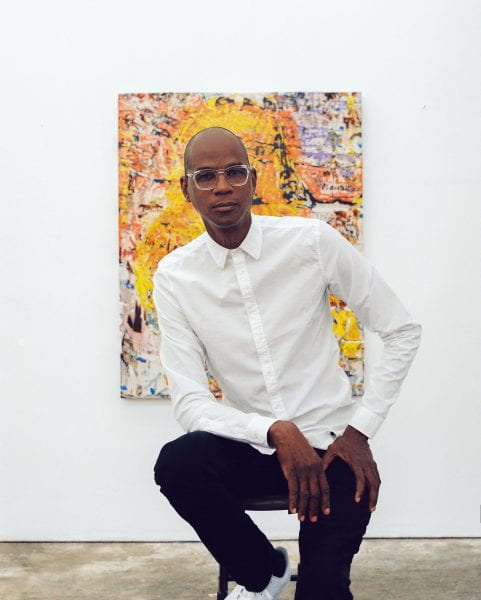

© Mark Bradford

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Mark Bradford, Minutes Are Painful (2016)

Written by Jenny Harris, PhD Candidate Department of Art History, 2027

Minutes Are Painful is a picture of words. Carved, stencil-like from the dense buildup of accumulated bits of paper, its letters come in and out of view, yielding only fragments of legibility: Ameri-, establishment, the free, thereof, of the pres-, the right of the, and so on. The work is one of Bradford’s “Amendment Paintings,” a series that features the written contents of each of the first ten amendments of the United States Constitution, known collectively as the Bill of Rights. Here, Bradford considers the first amendment, which guarantees religious protection, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and the right to petition the government.

At the Rubenstein Forum, Bradford’s painting is installed with the original newspaper printings of the constitutional amendments that would eventually become the Bill of Rights. Bradford, who has made paintings with paper since the early 2000s, seized on the material connections between the historic document and his own work. Though considerably larger in scale, Minutes Are Painful, like the Bill of Rights, is made primarily of paper. After scavenging the material in his native Los Angeles, Bradford typically subjects it to an elaborate process of accumulation and erasure: ripping, soaking and pulping it, then layering it thickly onto the canvas surface and fixing it with clear shellac. Next, he sands it down, scratches and slices through, tears away, and paints over. This labor-intensive approach ultimately yields a surface that is both densely layered and highly textured. Indeed, Minutes Are Painful has a hard-won, even lacerated quality that evokes the somber tone of its title and the violence of the nation’s past. Like this painting, whose grounds are formed by raw and battered paper, American independence was premised on acts of harm and destruction. Bradford never makes such parallels explicit, but instead uses the language of abstraction to evoke the ghostly presence of American histories of slavery and settler colonialism, a reminder that they remain embedded in our founding documents.

That the text of the amendment is only partially legible is key to understanding how Bradford engages with such historical objects. “Certain words flow in and out,” he explains, “they’re legible and not legible, they hint, but in some ways that’s how we really do understand the dense documents. We will never fully understand. They’re so dense, but we pull, and we glimmer, and we dive, and we project onto those documents.” Guided by questions about American history and its intersections with race, class, and gender, Minutes Are Painful is exemplary of Bradford’s commitment to pursuing a socially committed mode of abstract painting.

Read More

Bradford’s use of the First Amendment might be situated in relation to the particular moment in which he made the work: a year when the unceasing and increasingly visible violence directed against black bodies prompted debates not only about the health of the country, but more specifically, about the supposedly foundational American rights of freedom of speech and of assembly or protest. It was in 2016 that San Francisco 49ers quarterback, Colin Kaepernick decided to kneel rather than stand during the broadcast of the national anthem—a decision that sparked a series of similar gestures of protest that unfolded across national sports teams over the course of two and a half years. The gesture—though premised on American freedoms—was also met with considerable backlash and efforts to silence such forms of free speech. In the same year, Donald Trump, who would soon be elected President, attempted to silence his opponent, leading a chorus of demands to “lock her up!”

To understand Bradford in this context, however, is to see how abstraction has allowed him to stage a particular form of political speech. On the one hand, it freed him from the expressive limitations of figurative or representational painting—as he puts it, “to speak out the side of my neck [and] to practice a form of indirect speaking.” At the same time, Bradford brought to abstraction a particular set of political concerns that extend beyond the traditionally hermetic, often purely aesthetic concerns of the canon. Reflecting on his decision to begin working abstractly, the artist noted, “I just thought I was going to do abstract work, but it was going to talk about race, class, culture, and all these things, but I was going to do it from an abstraction place, which gave me freedom. Then I was going to look outside…. I was going to have a relationship with the world and with politics because I was interested in those things.”

In 2016, Bradford directed these concerns to the legal document designed to protect Kaepernick’s speech. “I was really starting to get very interested in the foundations of our country,” he explained. “The Amendments, or the Bill of Rights, are still what we go to.” For him, revisiting the 1791 document 225 years later meant tearing it apart—rendering it fragmented, incoherent, battered. Minutes Are Painful takes the first amendment and refuses to let it cohere; it asks us to see its guarantee as fragile and broken rather than synthetic and whole. In this way, the work’s imposing scale and tactile physicality confront its viewer with a challenge: to account for this historic document not simply as a thing of the past, but as living and therefore, precarious thing.

Bradford’s abstract canvases build on several art historical precedents, from décollage, a strategy deployed by artists in France following World War II involving the tearing and cutting away of paper, to the more recent language-based paintings of American artist Glenn Ligon. More broadly, however, Bradford’s work extends a long history of African-American abstraction that has often been downplayed or overlooked in the history of twentieth century modernism. As art historian Sarah Lewis has written, “For decades, it had been difficult to even see the work of African American abstract artists in mainstream histories and exhibitions. Yet it is not possible to fully understand the history of the field of late modernism (or African American art at large) without considering the history of black abstraction.” By making social and racially charged material the subject of abstract paintings, Bradford not only brings such topics to the fore, but asks us to interrogate their layered and obscured histories both in and beyond the sphere of art.

If Bradford’s socially committed practice can be located in the folds of his lacerated paper canvases, it likewise extends beyond their confines in the form of community-oriented enterprises and initiatives. A lifelong resident of Los Angeles, in 2014 Bradford founded Art + Practice, a community-based organization that offers foster youth of Central L.A. access to both social services and internationally recognized contemporary art, providing a platform for the exchange of ideas about art and culture. And in 2017, on the occasion of his exhibition, “Tomorrow is Another Day,” at the 57th Venice Biennale, Bradford established Process Collettivo, an initiative that partnered with a local women’s prison, raising awareness about the issues faced by Venice’s incarcerated population and supporting its members in the transition to post-prison life. With these socially-committed projects, Bradford joins a growing group of contemporary artists who put their cultural capital to work, bridging the divide between the historically exclusive art world and their own local communities.

Artist Profile

Mark Bradford

American, born 1930

Written by Jenny Harris, PhD Candidate Department of Art History, 2027

Mark Bradford (b. 1961, Los Angeles) is best known for his monumental abstract paintings, which expand the medium through oblique references to the world beyond his studio. Paper, a humble and everyday material, is key to the larger social aims of such works. His earliest paintings he incorporated end papers (small translucent strips used in hairdressing), but has since expanded to incorporate a wide array of printed matter, including newsprint, maps, and “merchant posters,” advertisements that litter the urban landscape. After scavenging such material, Bradford engages in a process of accumulation and erasure: ripping, soaking and pulping it, then layering it thickly onto the canvas surface and fixing it with clear shellac. Next, he sands it down, scratches through, tears away and paints over. This labor-intensive process ultimately yields a surface that is both densely layered and highly textured.

Bradford’s art has always used the language of abstraction to explore the relationships between American politics and its historical, often ugly, intersections with race, class, and gender. He was recognized for this work in 2017 when he was selected to represent the United States at the 57th Venice Biennale, the most prestigious international festival of contemporary art. In the same year, he debuted Pickett’s Charge, a monumental panoramic work designed for the Hirschhorn Museum’s rotunda that describes the final assault of the Battle of Gettysburg, a turning point in the American Civil War. In 2018, he completed a work entitled We The People, comprised of 32 canvases with text from the United States constitution which is installed permanently at the U.S. Embassy in London.

A lifelong resident of Los Angeles, in 2014 Bradford founded Art + Practice, a community-based organization that offers foster youth of Central L.A. access to both social services and internationally recognized contemporary art, providing a platform for the exchange of ideas about culture.