John Pine’s Engraving of the Magna Carta (1733)

Written by Brandon Truett, PhD ‘20

On October 23, 1731, the Cottonian Library in Westminster, which later became the core of the British Library’s collections in 1753, suffered a devastating fire that affected at least 100 of the treasured books and manuscripts. The library’s copy of one of the few surviving copies of the 1215 Magna Carta narrowly escaped total incineration. Arthur Onslow (1691-1768), speaker of the House of Commons, led an effort to ensure the preservation of the document. In 1733, the talented English engraver John Pine (1690-1756) was commissioned to produce a facsimile of the library’s Magna Carta, which is now on display at the David Rubenstein Forum.

Pine was an accomplished engraver of maps and illustrated books, and his engraving of Magna Carta demonstrates one of the most magnificent achievements of his artistic career. Pine created the copperplate facsimile by duplicating the medieval Latin script of Magna Carta in the center with the addition of several embellishments, particularly the colorful coat of arms of King John’s twenty-five barons that flank the document on both left and right vertical borders. The first edition of the engraving was impressed on vellum, of which this is one; a later edition was made on paper by his son Robert Edge Pine.

Magna Carta, or Great Charter, was first issued in 1215 as a “peace treaty” composed of sixty-three legal provisions between King John and his barons that aimed to curb unchecked royal power that had enabled the King’s many crimes. For over 800 years, Magna Carta has remained one of the most discussed historic documents in Western culture, far surpassing its original medieval context. However, scholars debate the extent to which the provisions of the Magna Carta have shaped subsequent legal doctrine. As indicated by Pine’s symbolic engraving, it is undeniable that Magna Carta exists as a talisman, one that commentators have wielded for centuries to provoke inquiry into a range of political issues.

Read More

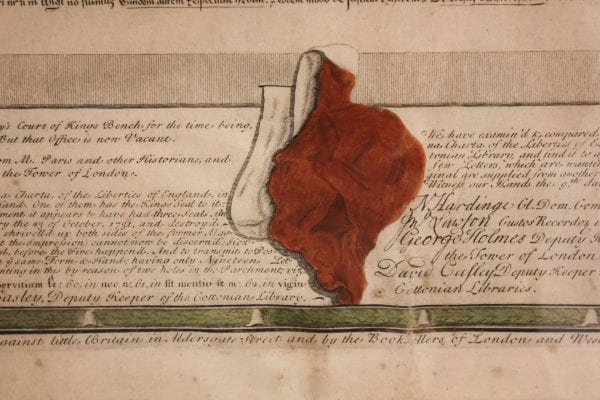

Pine’s attention to detail can be visualized most strikingly by King John’s burnt red wax seal at bottom center, reminding us of the damaged state of the original document.

While the script seems to provide an imaginary view of Magna Carta unmarred by the fire, the melted seal draws our attention to the fragile materiality of parchment as it weathers through time. As the only full and accurate transcription of the 1215 Magna Carta, Pine’s engraving served as the model for William Blackstone’s hugely influential printed copy that appears in his scholarly book The Great Charter and Charter of the Forest (1759), which analyzes the document’s complex medieval history from 1215 to 1300.

The political climate of thirteenth-century England was turbulent to say the least. The hateful reign of King John threatened to embroil the kingdom in bloody civil war. To redress the king’s wrongdoings, the twenty-five barons drafted through negotiation the sixty-three clauses that constitute Magna Carta, guaranteeing and protecting the rights of the clergy and men of nobility. Many scholars understand the importance of Magna Carta as resting in its promise to instantiate heretofore unwritten law into the written word. Indeed, the most oft-cited clause of Magna Carta sought to prevent the king from imprisoning or killing his political opponents without reason— what is now known as due process of law. It is important to remember that this provision, among the many others, was not enacted in 1215. Magna Carta was reissued several times by subsequent kings, notably in 1225 by Henry III and in 1297 by Edward I. Within weeks of applying his seal in 1215, King John nullified Magna Carta. As the historian Nicholas Vincent contends, “Magna Carta, the treaty that failed, was cosigned to oblivion … so much scrap parchment for rats to nibble at.”

So why has Magna Carta remained such a symbolic historic document of freedom? The long history of re-examining and displaying Magna Carta as a relic helps us to understand the ability of the written word to make things happen in the world. In an article for The New Yorker to commemorate the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, historian Jill Lepore reflects on the ways that commentators throughout history have instrumentalized the document to different effects. In the history of the United States, as Lepore explains, “Magna Carta has a special lastingness.” For instance, Lepore quotes Justice Antonin Scalia who once proclaimed that “It is with us every day.” Delving into Magna Carta’s persistence beyond medieval England provides a fascinating story about the ways in which material documents travel and make meaning across different cultural contexts.

More specifically, Pine’s engraving of Magna Carta invites viewers to think about the historical moments in which the relic seemed to illuminate most radiantly, provoking artists and legal theorists to make use of it. In eighteenth-century England and colonial America, as Lepore points out, the charter was brandished as “an instrument of political protest.” Just as Pine embeds the icon of Magna Carta within an environment of colorful embellishments, eighteenth-century American colonists harnessed the visual and verbal power of Magna Carta to make their political arguments. For example, Benjamin Franklin referred to Magna Carta to substantiate his legal decision that the colonists could rightfully reject British Parliament’s Stamp Act of 1765, a bold move during the American Revolution that was popularized through the phrase “no taxation with representation.” Eighteenth-century U.S. newspapers were awash with references to Franklin’s transformation of the charter as a tool to defend the liberties of the colonists. Instead of using the text, Magna Carta also appeared as an image of protest during the time, such as Massachusetts’s 1775 seal.

In a 2016 article for the North Carolina Law Review, R.H. Helmholz evaluates these processes of “myth-making” that have shaped contemporary understandings of Magna Carta. An expert of medieval legal history, Professor Helmholz contends that, from the thirteenth to the eighteenth century, interpreters such as Edward Coke “understood that the words of a statute like Magna Carta could contain a principle capable of producing results greater than those that were readily apparent from its text.” Indeed, the magic of Magna Carta—the fact that it has sat at the center of legal debates for centuries––lies in the ways that commentators are able to see beyond the ink on parchment to find manifold meanings and applications of its words. With its stunning embellishments that direct the viewer’s eyes around the borders of the text itself, Pine’s engraving visually renders the totemic status of Magna Carta, showing how critical inquiry into a symbol of freedom and protest accumulates over centuries.