Jasper Johns, Flag (1960)

Written by Emily Kang, BA 2021

Flag is not as it purports to appear––a metallic image of the American flag. In an oft-cited interview from 1959, Johns declared that he works with “things the mind already knows,” or clearly recognized symbols, to push the viewer to explore various interpretations about how an artwork functions as an object. Appearing in over 100 works, the icon is divorced from its patriotic function, and fills the canvas in its entirety. Flag appears to exist in, as Leo Steinberg describes, “a perpetual waiting… [as a] token of human absence from a man-made environment.” This artwork challenges the viewer to reconsider the flag outside of patriotic contexts and within the expanded visual field of cultural signs, images, and objects.

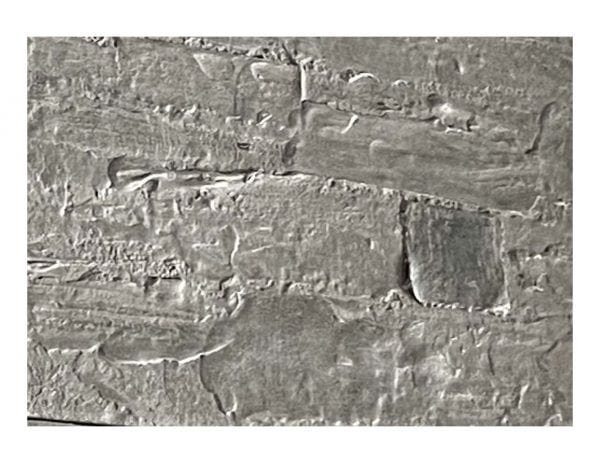

Johns is known for defying the boundaries of both painting and sculpture. Johns first appropriated this American icon through the use of encaustic with Flag (1954-55). Shortly afterward, Johns began to experiment with Sculp-metal, a putty-like material containing aluminum powder that can be spread across a canvas or other materials to give an illusion of being entirely metal; he created Lightbulb (1958). This transition from canvas to sculpture marks a pivotal moment in Johns’s career as his interrogation of objects and materials evolves.

This is the only flag for which he uses Sculp-metal. While Flag is formally categorized as a painting, the thickly applied layers of opaque Sculp-metal form blankets over found objects and other print material beneath the surface, imbuing this work with an illusory sculptural quality. In the lower right, edges of a postage stamp are clear, indexing deeper layers of print material beneath the surface of Sculp-metal. Also concealed is the painted dedication on the back that declares: “For R. Rauschen – / berg –– promised / ca. 1957 / J. Johns 1960.” This hidden dedication bespeaks not only the intimacy that existed between the two artists but also the vibrancy of their working relationship—always in proximity to one another in mind and space.

The rationale behind Johns’s selection of the flag as an American icon is subject to much debate. Johns has resisted fixed interpretations of both his artwork and his identity, stating that the idea of painting the American flag simply came to him in a dream, thus holding open the various significations between viewers and the times in which they encounter his artwork.

Read More

With Flag (1960), Johns departs from his earlier use of encaustic, a painting technique involving hot wax mixed with vibrant pigments, which he then applied over scraps of paper and fabric. Johns’s use of Sculp-metal, a popular material with hobbyists and modelers in the 1950s, is therefore in line with the artist’s proclivity for unconventional materials. Johns’s choice of materials integrates amateur and professional artistic fields, challenging defined notions of “high art.” At the same time, Sculp-metal allows Johns to capture textural details with stunning accuracy. In a rare interview explaining his decisions, Johns noted the importance of this clarity with the postage stamp, explaining that he wanted it to be visible as a way to “anchor [the Flag] in reality.” Simultaneously, layers of newsprint that constitute the texture of the flag’s stripes are indistinguishable from the Sculp-metal. The relative legibility or illegibility of the discursive components of Flag complicate its always already ambiguous status as icon.

Johns’s selection of the American flag unfolds amid the Lavender Scare of the 1950s, a period of moral panic tied to McCarthyism and the Second Red Scare that viewed gay men and lesbians as communist sympathizers and thus a threat to national security. In 1953, President Eisenhower enacted Executive Order 10450, which barred gay men and lesbians from employment in federal agencies, including the armed services. In the same year Johns had returned from two years of service in Korea. Just a year later in 1954, Johns would choose the icon of the American flag as subject matter for his first Flag (1954-55).

Just as the opaque Sculp-metal raises questions as to what lies beneath the surface, the social and historical contexts of the artwork’s production ask us to reconsider the conventional art-historical narrative surrounding Johns’s early career. As the painted dedication suggests, the work was a gift to the American artist Robert Rauschenberg, who, in 1990, Johns described as “the most important to me and my thought.” The two artists are known for their roles in shaping American Neo-Dada, an art historical movement that recalls early 20th century Dada through the use of found materials and absurdist cultural reference-making. Johns and Rauschenberg collaborated on commercial projects to make ends meet and were actively and intimately involved in each other’s artistic practices. Notably, gallerist Leo Castelli stopped in to see Rauschenberg about a planned exhibition when Castelli mentioned hearing about an elusive young artist named Jasper Johns. Since Johns lived in the same building, Rauschenberg introduced the men on that day. Castelli, so taken with Johns’s work, immediately pivoted from a Rauschenberg show to a Johns show that featured the first Flag and launched his career. Rauschenberg requested a flag from Johns in 1957 and was gifted this unique artwork in 1960. This oft-cited narrative of a professional relationship and personal friendship fails to fully recognize the two artists’ complex intimacy that lasted until their falling-out in 1961. In 1993, Jonathan Katz first explicated the importance of Johns and Rauschenberg’s relationship to the development of their artmaking, arguing that “they formed a new pictorial language, new symbol systems, new subjects—and a new subjectivity in painting.” Katz’s careful attention to the ways both artists coded their homosexuality in their artworks opens potential avenues to apprehend Johns’s Flag and its hidden painted dedication as forms and actions of same-sex desire. The artists actively watched each other’s practice, sometimes contributing but always learning from each other’s art in ways that testify to a kind of revolutionary intimacy.

While the relationship between Johns and Rauschenberg is physically included with this dedication, it is hidden from view, leaving it as a private sign between two men.

The transformation of cultural objects and the fluidity of abstraction are both central to queer art. In addition to the prominent postage stamp in the lower right of Flag, newspaper scraps are used to build up the stripes of the flag. The newspaper evokes the materialization of language and the principle of free speech, whereas the stamp indexes the U.S. Postal Service and thus the mechations of state governance. However, the layers of Sculp-metal that conceals both print materials complicate how we conceive of their meanings. The painted dedication on the back of Flag offers yet another example of hidden communication. While the relationship between Johns and Rauschenberg is physically included with this dedication, it is hidden from view, leaving it as a private sign between the two men. Other viewers unaware of this dedication would have had a very different experience of this artwork. These signs of furtive communication raise questions about what can and cannot be said in the public sphere and how those words might be expressed in codes that we are asked to decipher. In light of Anne Wagner’s recent consideration of how Johns’s flags critique ideas about the mid-century emergence of U.S. global hegemony, the painted dedication might be interpreted as indexing the problematic relation between the gay citizen subject and the nation-state.

When Johns’s art debuted during the tumultuous postwar period, controversy arose about whether the use of the flag was unpatriotic. The directness of Johns’s painted dedication guides critical inquiry into the cultural prejudices and legal limitations that have historically circumscribed the rights of LGBTQ-identified citizens to free speech and personal expression. Today, as the artistic and political climate continues to shift, new interpretations of Flag emerge, from meditations on the object status of art in late-stage capitalism to the queerness of Johns and Rauschenberg’s art-making. These critical approaches do not lend themselves to any singular interpretation of the artwork. Rather, they emphasize the way that the disarmingly straightforward appearance of Johns’s Flag in fact provides the richness of interpretation.

Artist Profile

Jasper Johns

American, born 1930

Written by Emily Kang, BA 2021

Born in Augusta, Georgia in 1930, then raised in South Carolina by his grandparents, Jasper Johns inherited a love of art early on from his grandmother, a painter. Johns briefly studied at the University of South Carolina as well as the Parsons School of Design before serving in the US Army during the Korean War. When he returned from the war in 1953, Johns settled in New York.

In 1954, Johns destroyed nearly all art he had made up to that point, stating that it was time “to stop becoming and to be an artist.” From here, he began his famous flag and target series. Restrained, ordered, and systematically constructed, John’s encaustic paintings stood in shocking contrast to contemporaries in the Abstract Expressionist movement when his work skyrocketed into the public eye with his first solo show in 1958.

Johns works in the intersection of contradiction: His work appears literal and his subjects mundane, but it draws on complex ideas. This contradiction becomes a key theme throughout his oeuvre. Along with Robert Rauschenberg, Johns is considered a founder of American Neo-Dada and a key force in the development of Pop Art, making him one of the most influential modern American artists.

Related Links

University of Chicago Booth School of Business Art Collection: Pao Soft (2010) Danh Vo

Professor Darby English: Two of a Kind

Professor Bill Brown: Things, a special issue of Critical Inquiry, Fall 2001 (Book version 2004)