U.S. Constitution – First Day Public Printing (1787)

Written by Fiona Maxwell, PhD Candidate, Department of History, 2024

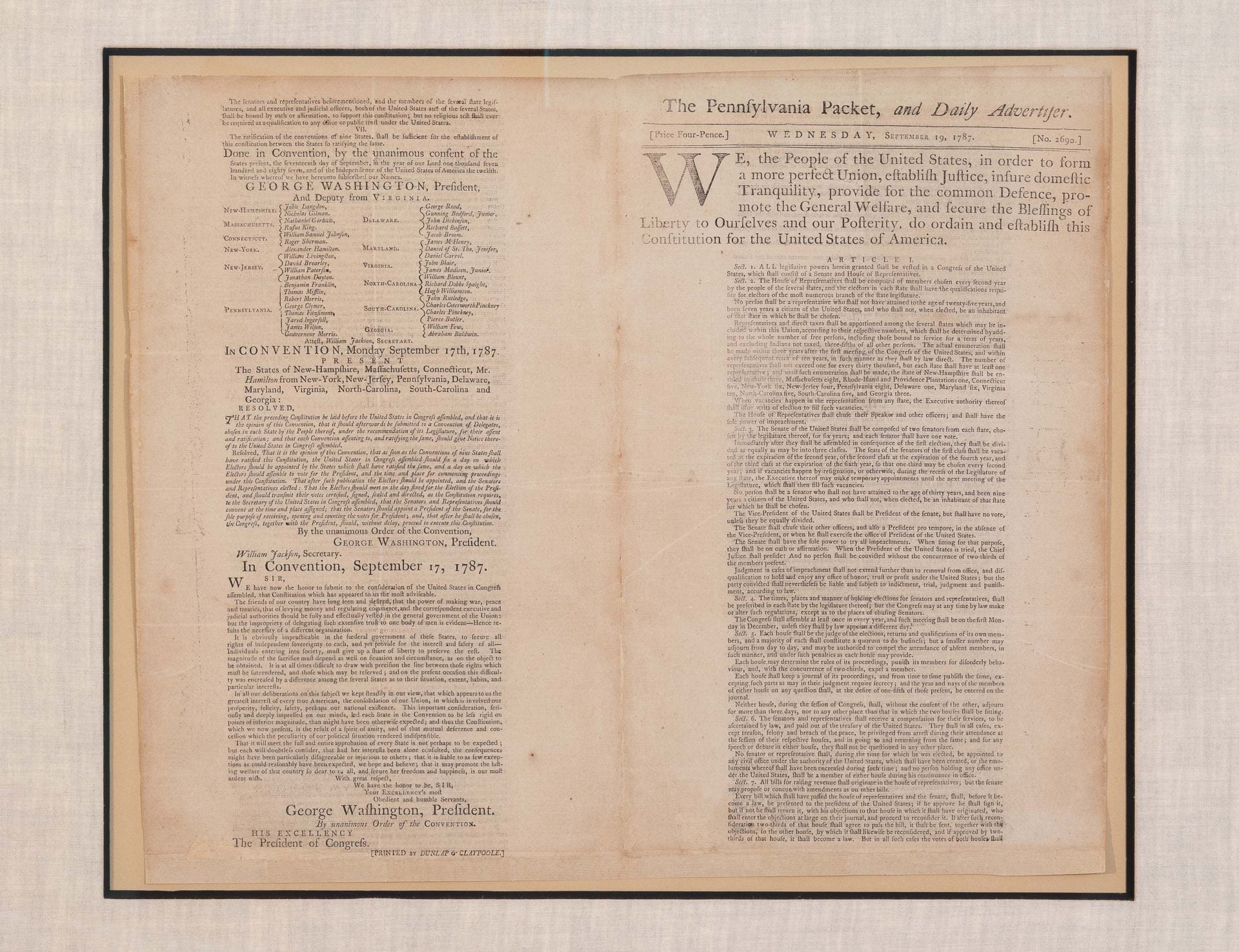

On September 19, 1787, the Pennsylvania Packet placed the text of the United States Constitution before the American public for the first time. The delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia signed the Constitution on September 17 and forwarded it to Congress in New York, along with a resolution that called for its submission to the state legislatures for ratification. The official printers of the Convention, John Dunlap and David Claypoole, were also the proprietors of the Packet, a daily Philadelphia newspaper. Following the first public reading of the Constitution in the Pennsylvania General Assembly on the morning of September 18, Dunlap and Claypoole began work on a “special issue.” They had previously printed two drafts of the Constitution: one for delegates to reference during the Convention, and a final version that was sent to Congress. Except for the enlarged preamble, the text for the Packet used the same typesetting as the official Congressional printing.

The September 19 Packet shows how the politics and culture of print media influenced the Constitution’s origin and structured its dissemination. As the first publication of the Constitution that was intended to be read by the citizenry, this newspaper printing highlights the role of reading in a democracy. Many eighteenth-century Americans initially encountered and studied their new system of government through newspapers. The print publication of the Constitution launched the ratification debates, which ended in 1792 with the adoption of the Bill of Rights. Since then, successive generations of readers have assumed the task of putting constitutional theories into practice. U.S. citizens have continually turned to this foundational text for answers to legal, political, economic, and social questions, remaking its meaning in the process.

Read More

The appearance of the United States Constitution in the Pennsylvania Packet was one of many media events that propelled the formation of the federal government and garnered a global audience for the new nation. The initial publication of the Constitution ushered in a period of intense deliberation that unfolded through the reading, writing, and distribution of printed materials. The adoption of the Bill of Rights in 1791 brought an end to this flurry of print politics, but the international ramifications of reading the Constitution had only just begun. The United States was the first country to craft a complete written national constitution. Within one month after its publication in the Packet, the text was circulating abroad. In its immediate aftermath and for centuries to come, the U.S. Constitution inspired nations around the world to produce written constitutions of their own.

As a printed document, the U.S. Constitution promoted a new vision of popular sovereignty that invested authority in everyday readers. The Constitution professed an anonymous authorship and evolved through a long process of collective debate and revision. While the 1776 copy of the Declaration of Independence enjoys a unique symbolic place in the national imagination, every printed copy of the Constitution, beginning with this first-day printing in the Pennsylvania Packet, possesses equal significance. Whenever we read the text of the Constitution, we participate in reaffirming its legitimacy and transforming its meaning.

To understand the origins of this transformational document, Eric Slauter, a professor of English at the University of Chicago, argues that we must delve deeply into eighteenth-century Anglo-American politics and culture. In The State as a Work of Art, Slauter places a traditional archive of printed texts in conversation with “the wider verbal, visual, material, and performative cultures of the revolutionary period.” Slauter’s innovative approach uncovers the ways in which Revolutionary Era Americans simultaneously “described constitutions as products of their people and people as products of their constitutions.” The U.S. Constitution, Slauter demonstrates, cannot be fully comprehended without exploring the complex cultural frameworks that shaped its crafting and acceptance.

University of Chicago law professor David Strauss similarly connects the Constitution to its political and cultural context by tracking the ways in which U.S. constitutionalism has evolved alongside historical developments. Strauss describes the United States as a common law system with a “living Constitution.” While he acknowledges that the original document protects “fundamental principles against transient public opinion,” he asserts that past decisions and practices are as meaningful as the original written text. Tracing the Constitution’s journey across the changing backdrop of United States history illustrates that the Constitution is solid, yet malleable – a product of its time, yet responsive to evolving circumstances.

The process of investing the Constitution with new meaning began as soon as the original generation of founders no longer presided over U.S. politics, law, and print media. Alison LaCroix, also a law professor at the University of Chicago, studies the “second generation” of founders who put “the theories of the Constitution into practice.” Her forthcoming book, The Interbellum Constitution, cites the “Long Founding Moment” from 1815 to 1861 as a rich and underappreciated period when readers engaged with the Constitution and remade its meaning. The United States faced unprecedented challenges during the interbellum era, including industrialization, economic recessions, westward expansion, movements for racial and gender equality, and sectional friction over slavery. Issues that had not been present when the framers drafted the Constitution “put pressure on the original understandings that underpinned the words of the written text,” LaCroix notes in a 2013 article for the University of Illinois Law Review. Yet, the Constitution pervaded public discourse and structured the ways that nineteenth-century Americans approached legal, political, economic, and social questions. By using the Constitution to map “the future path of a nineteenth-century democracy,” the second generation of founders represents an early group of readers who added new meaning to the “living Constitution” of the United States.

Readers have added to and transformed the meaning of the Constitution in crucial ways, most notably by investing the document with emancipatory potential. The thinking of former enslaved man and abolitionist Frederick Douglass evolved from condemning the Constitution as a proslavery text to defending its antislavery principles. After escaping from slavery, Douglass aligned with white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, the founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Garrison and his supporters advocated abstaining from political participation. They believed the Constitution was irrevocably tainted due to its tacit sanctioning of slavery, most notably in the clause that counted three-fifths of all slaves when distributing representation in Congress. Douglass initially adopted Garrison’s view. In 1847, he announced to the Anti-Slavery Society that he wished to see the “Constitution shivered in a thousand fragments.” Then, in 1850, Douglass encountered an antislavery interpretation of the Constitution promoted by abolitionist Gerrit Smith. After engaging in careful study and consideration, Douglass split with Garrison in 1851. Douglass openly embraced participating in the political process to promote abolition, and he reframed the Constitution as an antislavery document. In his 1852 speech, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” Douglass proclaimed that “interpreted, as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a glorious liberty document.” Douglass’s radical rereading was a rebuke to Garrisonian abolitionists and proponents of slavery alike, who saw in the Constitution a legal defense of slavery.

It would take a war and three Constitutional amendments to fully realize an antislavery reading of the Constitution. In the years leading up to and during the Civil War, the prevailing interpretation stated that slavery was a state institution and could not be abolished by the federal government. Even though this idea was not specifically outlined in the Constitution, it was widely accepted and constrained the legal strategies available to abolitionists. After the Union won the Civil War in 1865, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments abolished slavery; guaranteed birthright citizenship, including for African Americans; and prohibited the denial of the vote to any citizen based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” These Reconstruction Amendments transformed the Constitution into a new document – one that was much closer to the “glorious liberty document” that Douglass envisioned.

Frederick Douglass invested great authority in readers and their political acts of interpretation, arguing that “every American citizen has a right to form an opinion of the constitution.” From the moment of its first printing in the Packet, it has been the task of readers to bring the Constitution to life.